The Shady Double Life Of Dr. Oz

After Dr. Mehmet Oz made his first appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show in 2004, his career took off. His partnership with Winfrey led him to launch The Dr. Oz Show on the Harpo Network in 2009, and now he's a household name — as well as a guy who seems to be constantly trying to sell you a "natural" weight loss pill that works like a "miracle."

Those "miracle" and "magical" cure claims ended up landing Dr. Oz in a world of controversy, which even saw him have to go before Congress to explain himself. Years later, and after battling both public detractors and colleagues within the medical field, Dr. Oz and his show are still going strong, but his reputation certainly hasn't gone unscathed.

While it seems like Dr. Oz is here to stay for the time being, it's clear that viewers should now take his advice with a grain of pure, unadulterated, red Hawaiian sea salt. In the meantime, let's dive right in to the double life of one of the most well-known doctors in the world.

It's a miracle this didn't bring him down

Dr. Oz referred to green coffee extract as "the magic weight-loss for every body type," and cited "scientists" as agreeing with him. He called Raspberry Ketone "the number one miracle in a bottle to burn your fat," and referring to Garcinia cambogia, he said, "It may be the simple solution you've been looking for to bust your body fat for good."

For the record, there's no science to back up any of those claims—in fact, studies have indicated otherwise. A 1998 study showed that Garcinia Cambogia didn't notably help participants lose weight; a similar 2013 study proved the same for green coffee; and there isn't enough data on raspberry ketone to indicate much of anything either way. In fact, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) sued the company that makes green coffee extract. Sorry, folks, good old-fashioned diet and exercise continue to be the only way to successfully lose weight naturally.

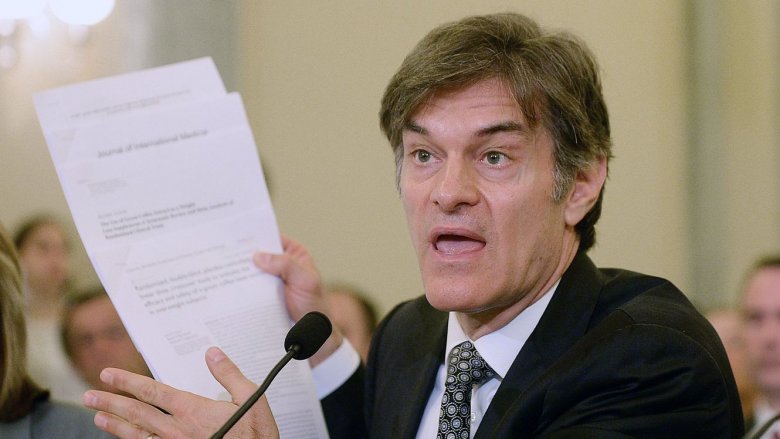

Dr. Oz goes to Washington

After accusations of misleading his audience about various weight-loss products, Dr. Oz was summoned to face a Senate subcommittee in 2014. He promptly began to backtrack on his claims. While he never referred to his comments as outright lies, he did concede that his language was a little strong (e.g. using words such as "miracle" when referring to a pill that will likely do nothing at all). "I'm in a position where I'm second-guessing every word I use on the show right now," he told Sen. Claire McCaskill, according to The Atlantic. "I'm very respectful, I've heard the message, I've told my colleagues at the FTC, I get it."

While it may have sounded like the Senate's rebuke of Oz was rather scathing, The Washington Post reported that the hearing "didn't really come to a conclusion." In fact, Oz actually suggested that he always recommends a healthy diet and exercise along with any supplement regimen, which he went right back to promoting on his show just days later.

Passing the buck

After his Senate appearance, Dr. Oz started backtracking from his once conciliatory stance. In an April 2015 interview with NBC News, Oz said his show is "not a medical show" and defended the title by giving a convoluted justification about the logo. "It's called The Dr. Oz Show," he said. "We very purposely, on the logo, have 'Oz' as the middle, and the 'Doctor' is actually up in the little bar for a reason. I want folks to realize that I'm a doctor, and I'm coming into their lives to be supportive of them. But it's not a medical show." Alrighty.

The good doc then went on Fox & Friends (via Mediaite) a month later and continued to pass the buck. He told host Elisabeth Hasselbeck that while he wished he'd "never used the laudatory terms [he] used for weight loss supplements," he placed a lot of the blame on unscrupulous marketers who "hijacked" his messages and allegedly stole his name and likeness to sell their products online.

Oz then said that he does "toggle back and forth between hard core medicine" and alternative options that "might be helpful." He continued, "It's not a medical press show. My job is to take America and elevate the conversation."

The most luxurious, fabulous presidential physical ever

In the lead-up to the 2016 Presidential Election, many reporters, talk-show hosts, and others were criticized for the allegedly softball approach they took when interviewing then-presidential candidate Donald J. Trump.

Some outlets, such as Politico, took particular issue with Trump's appearance on The Doctor Oz Show, which aired at a time when rival Hillary Clinton's health was being widely debated in the media. "For Donald Trump, Oz's show proved to be a safe space, a haven shielded from any tough questions or follow-ups, and offered Trump a platform to offer up whatever he wanted, from saying that he feels as good as a 30-year-old to playing up his stamina and his [testosterone] levels," Politico said.

The episode was also criticized for unveiling Trump's medical records, which were two sheets of paper, and the questionable on-air physical that Dr. Oz conducted on the soon-to-be President. "[There were] no actual exams, no hands laid on the patient, no verification of the patient's data. Just a series of questions and the two pieces of paper from Trump — authored by none other than [Trump's longtime doctor] Harold Bornstein," Vox wrote, calling the episode "surreal" and "disturbing."

Dr. Oz has defended this segment: "Why not release [Trump's medical records] on a show that talks to people every day about health and have some context put on the results?"

The 'Dr. Oz Effect'

When Dr. Oz tells his millions of viewers to buy a product, they listen. Science Based Medicine calls this phenomenon the "Dr. Oz Effect," noting that when he promoted green coffee bean extract (GCBE) on his show along with "naturopath" Lindsey Duncan, they directed consumers to websites owned and operated by Duncan. Duncan subsequently sold a reported $50 million worth of the "weight-loss supplement," in spite of the FTC's later discovery that Oz "had no familiarity with the purported weight-loss benefits of GCBE" prior to producers approaching him to be their "expert" for a segment on The Dr. Oz Show.

Is it possible that Duncan pulled the wool over Dr. Oz's eyes? That's hard to believe considering that during Oz's senate hearing, he claimed the he does "passionately study" the products he endorses on his show, so why would he not extend that same academic due diligence to his "expert" guests?

What's possibly worse, according to Forbes, is that "The Dr. Oz Effect" could be leading viewers to engage in a form of "hypochondriasis," meaning they self-diagnose based on the limited information presented by Dr. Oz or other TV docs. The viewers then simply look to the supposed "miracle cures" to address their symptoms, rather than consulting a physician to do a thorough investigation of what could be a serious health issue.

However, when the makers of products like Neti Pots enjoy a staggering 12,000 percent rise in sales after a Dr. Oz endorsement, it's going to be awfully tough to sway them from using the wildly effective, yet dubious marketing technique of getting a TV doctor to say that firehosing one's sinuses with salt water is some kind of magical cure for congestion.

The real magicians are his lawyers

Perhaps unsurprisingly, some of the consumers who plunked down hard-earned cash on Dr. Oz's "miracle" supplements ended up unhappy with their purchases, most notably the aforementioned consumers of Lindsay Duncan's GCBE products, who ended up forcing the "naturopath" to pay back "$9 million in refunds" after the FTC found the marketing of those products to be "deceptive."

In 2016, TMZ reported that Dr. Oz was also named in a class action suit by a consumer who purchased the faulty weight-loss supplement Garcinia cambogia. The customer claimed Dr. Oz sold the product by saying it could be the "magic ingredient that lets you lose weight without diet or exercise." A representative for The Dr. Oz Show said the lawsuit attacked Dr. Oz's right to freedom of speech and argued that the show "does not sell these products, nor does [Dr. Oz] have any financial ties to these companies."

It wasn't just everyday consumers who came for Dr. Oz. Trade groups representing big manufacturers also wanted a piece of him. In 2016, Dr. Oz was also sued by the North American Olive Oil Association over his claim that 80 percent of the extra virgin olive oil purchased in supermarkets "isn't the real deal." Ultimately, the lawsuit, which was filed under the "Veggie Libel Statute" — We wish we were making that up — was dismissed, but it begs the question: How shady do you have to be for "Big EVOO" to come after you?

Do all opinions really deserve a platform?

Dr. Oz came under fire for airing an episode debating reparative therapy (or, therapy used to change one's sexual orientation) in 2012. He invited a member of the controversial National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH) to the show and referred to that guest as an "expert."

The episode became so hotly contested that a number prominent LGBT groups, including GLADD, condemned The Dr. Oz Show in a public statement. "Producers of the Dr. Oz Show framed their program on so-called reparative therapy in a way that provided a lengthy platform for junk science. ... Although the show also featured guests who condemned the idea and practice of 'reparative therapy,' Dr. Oz himself never weighed in, and the audience was misled to believe that there are actual experts on both sides of this issue. There are not."

The statement also took aim at NARTH, saying, "NARTH co-founder Charles Socarides called gay people 'a purple menace that is threatening the proper design of gender distinctions in society.' NARTH says it supports clients who seek to 'diminish their homosexuality and to develop their heterosexual potential' through therapy."

To his credit, Dr. Oz did express his opinion on reparative therapy in a blog post published after the show aired. "I have not found enough published data supporting positive results with gay reparative therapy, and I have concerns about the potentially dangerous effects when the therapy fails, especially when minors are forced into treatments," he wrote.

Feeling nervous? Here, have a chickpea

In March 2017, Dr. Oz upset some of his social media followers when he posted a tweet suggesting that anxiety could be fought "naturally" with seven foods, including chickpeas and dark chocolate.

"Someone is going to abruptly discontinue their meds, thanks to your appeal to nature rhetoric. You are a threat to public health, Mehmet Oz," wrote one follower. "No. Stop. You're insulting my clients and making life so much harder for those of us that actually work in mental health!!!" added another.

The incident was also cited in Forbes magazine's May 2017 piece titled "America, We Need To Break Up With Dr. Oz." "It might seem harmless at first glance, but suggesting that anxiety disorders can be treated with food is irresponsible — these disorders affect millions of Americans and are often debilitating," the op-ed said. "Anxiety disorders are highly treatable with behavioral therapy and medication, but too many people suffer without treatment, largely because of common misinformation and a stubborn stigma. There is no proven food-based therapy."

Dr. Oz seemed to concur with Forbes' assessment just one year earlier in a post on his show's website that literally advocated for anxiety disorders to be treated with "help from your doctor or another healthcare professional," who likely would would not prescribe avocado toast to fight "fatigue, headaches, and trouble concentrating."

While Dr. Oz's tweet may have been yet another of his attempts to augment traditional medicine with alternative solutions, he failed to make that distinction.

There's good money in data

It's no secret that search engines sell your every click to marketing and advertising agencies. It's the reason your web browser becomes littered with ads for Fruit of the Loom the day after you buy some undies on Amazon.

The same principle applies to survey data, specifically in the case of a site called Real Age, which according to a 2009 exposé in The New York Times, claimed "to help shave years off your age" by asking question about your lifestyle habits, then making recommendations on how to lower your "biological age," which is often much higher than the one based on your birth year. If this sounds to you like exactly the kind of dubious pseudoscience that Dr. Oz comfortably advocates, then it won't surprise you to learn that he was a "spokesman and adviser" for Real Age. But it gets even better than that.

In order to take the Real Age survey to obtain your "biological age," participants had to enter an email address, which was turned over to pharmaceutical giants such as "Pfizer, Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline," who also had access to the participants' survey answers. What this created was a perfect marketing pipeline that the drug companies used to directly target consumers who suffered from disorders they claim to treat with their products. Is all of this legal? Probably. Ethical? Well, that's a whole other ball of ginkgo biloba.

Blindsided by science

The British Medical Journal published a study performed in 2014 by several researchers from leading Canadian universities who examined claims made on Dr. Oz's show and another medical daytime talk series, The Doctors. The study's findings stated that roughly four out of ten claims on The Dr. Oz Show were not supported by evidence or are in direct contradiction to scientific studies. Researchers were only able to find legitimate evidence to support around 46 percent of the recommendations on the show; 15 percent of Dr. Oz's claims were found to be in direct contradiction to scientific evidence, and no evidence was found for the remaining 39 percent.

The study went on to conclude that "consumers should be skeptical about any recommendations provided on television medical talk shows," and that viewers should make "decisions around healthcare issues" with the help of actual healthcare providers and not "media health professionals."

What it sounds like to us is that, at this point, taking medical advice from Dr. Oz is like foregoing culinary school and instead just doing whatever it is Guy Fieri has been doing to food on television for the past several years. But don't quote us on that light-hearted comparison. We don't need a crew of Canadian academics coming in here and shooting holes in our logic.

A company man first and foremost

One of Dr. Oz's main defenses against virtually all criticisms of his alternative medicine suggestions is that he does not profit in any way from the sale of these products, which as far as we can tell, is actually true. But thanks to the infamous Sony email hacks in 2015, some eagle-eyed researchers at Vox spotted what appears to be evidence that Dr. Oz wasn't opposed to a little profitable conflict of interest after all.

In an email from Dr. Oz to the CEO of Sony Entertainment, the company that produces the show, Oz suggested the media giant "leverage the Sony-driven success of our TV show into other arenas where Sony thrives, like health hardware." What this meant, according to Vox, was that Oz was entirely comfortable schilling products on the show that were made by another division of the company that produces the show.

Granted, there's no evidence to indicate that Dr. Oz would personally benefit from the sale of Sony's "health hardware," but he also makes no mention of comparing other brand's health hardware devices to those of Sony, which his objective approach to alternative wellness would ostensibly require.

Not everything Oz touches turns to gold

In May 2017, the New York Post reported that Dr. Oz's magazine, Dr. Oz the Good Life, was being cut down from 10 issues a year to a quarterly "bookazine," designed to rely more on reader revenue than advertising money — future issues would reportedly cost $12.

The move was spun in a positive light, with some of the blame being put on poor ad sales, according to anonymous sources."We're always looking at whatever the most relevant market is," president of Hearst Magazines, David Carey, told The Post, adding, "Dr. Oz is still tremendously popular with consumers."

Still, the switch came with a cost. The Post also reported that most of the magazine's 35-person staff was being laid off, including Editor-in-Chief Jill Herzig and Publisher Jill Seelig.

His fellow docs threw him under the bus

In 2015, a group of ten physicians wrote a letter to Columbia University, where Dr. Oz is vice chairman of the department of surgery, asking that he be removed from his post, reported CBS News.

"Dr. Oz has repeatedly shown disdain for science and for evidence-based medicine," the group wrote, claiming he's repeatedly "misled and endangered" the public. Columbia refused the request, saying it wouldn't remove Dr. Oz as vice chairman because the school is "committed to the principle of academic freedom and to upholding faculty members' freedom of expression for statements they make in public discussion."

Despite Columbia's defense of Dr. Oz, later that week, SERMO, "a social network for doctors," conducted a survey (via Live Science) over the call for his removal from the university. The results were not good for Oz: "735 doctors (57 percent) said Oz should resign from his faculty position at Columbia. 50 doctors (4 percent) said Oz should have his medical license revoked. And another 280 doctors (22 percent) said Oz should both resign from his position and have his license taken away."

Obviously, none of that happened. At the time of this writing, Dr. Oz is still on the air, still practicing medicine, and still on the faculty at Columbia, but it's pretty crazy to think that the literal face of medicine for American pop culture isn't even close to being supported by the majority of his professional peers.

Step right up, get your red palm oil here!

In addition to allegations of lying about numerous weight-loss products, Dr. Oz has also been accused of peddling other fraudulent items. According to HuffPost, Dr. Oz touted red palm oil, a Vitamin E supplement, as the "miracle oil for longevity." His exact description of the product was: "There's a secret inside the flesh of this fruit, extending the warranty of nearly every organ in your body. This mega-oil may very well be the most the most miraculous find of 2013."

Dr. Oz also claimed it could prevent dementia and Alzheimer's, reported HuffPost, despite there being no research to support that claim. In fact, Vitamin E supplements reportedly have no proven effect on these conditions, and a 2004 study shows that an increased intake of saturated fats, such as red palm oil, could potentially lead to cognitive decline.

HuffPost cited six other dubious products peddled by Dr. Oz that all follow a similar pattern: Oz calls them "magic" or "a miracle;" other doctors disagree; then science is unable to substantiate Oz's claims and, in some cases, suggests the product could do more harm than good.

And Dr. Oz doesn't just deal in shady supplements. According to Gizmodo, there is almost no corner of the woo market from which Oz shies away. Numerology, palm reading, and even psychic power get a national spotlight from from a medical doctor employed by one of the country's leading ivy league schools. Is he really just trying to be an objective investigator into health and well-being, or his Dr. Oz the P.T. Barnum of medicine?

Fore!

Out of all of the examples on this list of how Dr. Oz may not exactly be the good-intentioned wellness guru who enters our living rooms each day with a smile and a cool glass of kombucha, this fun anecdote may be the least relevant. However, it involves him maybe hitting a guy with a golf ball, then denying it, so we're including it, along with that photo up there, because seriously, how do we not use that?

Anyway, in 2014, TMZ reported that Dr. Oz was playing a round with family and friends when another guy drove his golf cart directly into his shot, resulting in the guy taking a hit to his right forearm. Oz and his crew then reportedly "tended" to the man who was "in a lot of pain" and "badly bruised" until an ambulance arrived.

Later, a "source close to Dr. Oz" told TMZ that Oz wasn't the one who fired off the arm-bruising tee shot, but they would not disclose who it was. What we really want to know is that when Oz was tending to the fellow golfer, did he offer any alternative solutions for the pain? Like a handful of chia seeds, or perhaps healthy kale smoothie and some soothing breathing techniques?

Team Oz has a deep bench

Author and journalist Bill Gifford wrote a 2015 column for The New York Times arguing that Dr. Oz was "no quack." Gifford explained that one of the doctors who tried to get Oz removed from his position at Columbia did prison time for Medicaid fraud and argued that even "evidence-based medicine," as referenced in the doctors' letter, was questionable at times.

Gifford also argued that the aforementioned study published by the British Medical Journal technically proved that only around 11 percent of Dr. Oz's claims have been proven false; not more than half, as previously reported. "The BMJ authors also didn't list the statements they examined and the evidence for or against," Gifford wrote, "so it's hard to know how serious these errors might have been."

In addition to Gifford's defense of Dr. Oz, it should be noted that on top of the Emmys Oz has won for outstanding informative talk show, he's also been honored — most recently as of this writing — by The American Turkish Society for "significant contributions and moral commitment to improving the lives of so many in the United States," as well as "voted a 'Doctor of the Year' by Hippocrates magazine," reported Forbes.

The question then becomes: How can Dr. Oz on one hand be so alienating to so many in his field, but on the other hand, be showered with praise by the remainder of his cohorts, not to mention beloved by millions of viewers?