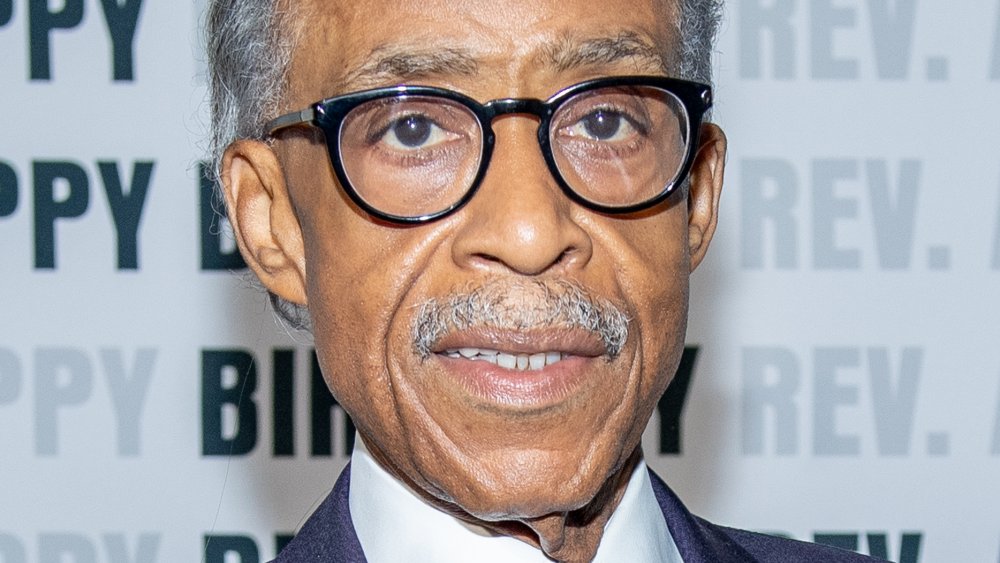

The Wild Real-Life Story Of Al Sharpton

Al Sharpton has been hailed and ridiculed his entire life — a paradox that largely defines him. Saturday Night Live lampoons him, but he has also hosted the show. While he is polarizing, especially on issues of race, nearly everyone can agree on one thing: he is a pistol! The Politics Nation host's undeniable charisma is a blessing and a curse. Some say he's the most influential civil rights leader today; others call him a huckster, eager only to draw attention to himself. But Sharpton's flair for the dramatic works, even if it makes him an easy punchline. Sharpton's thick skin developed at an early age, when he endured mockery after his father ran off with his 18-year-old half-sister. "I was conditioned for being ridiculed and controversial since I was nine," he told Vanity Fair.

Sharpton also works with anyone to forward a good cause, which sometimes makes for strange bedfellows is the sharply partisan world of U.S. politics. In fact, then-president George W. Bush thanked Sharpton for his "leadership" during a speech about Bush's landmark education policy No Child Left Behind. "Now, some of you are probably about to fall out of your chair when you know that Al and I have found common ground," Bush joked, adding, "He cares just as much as I care about making sure every child learns to read, write, and add and subtract."

Love him or loathe him, Sharpton is a prominent fixture in American politics — and his life has been a wild ride!

Al Sharpton ran for President in 2004

Al Sharpton began his career in politics as a primary candidate for New York's U.S. Senate seat in 1992, where he came in third but was not deterred. He lost the primary for New York's other U.S. Senate seat two years later and then lost the 1997 NYC mayoral primary, CNN reports. A track record like that would steer some people away from politics. Instead, Sharpton took a leap of faith and ran for president, but resigned his candidacy in under a year. He dropped out in March 2004 to endorse John Kerry, but that is unfortunately where his campaign's troubles really began.

The Federal Election Commission scrutinized Sharpton's campaign finance practices, found problems, and fined him. He also had to return the matching funds he'd received from the federal government because the campaign had exceeded spending limits. Even as he navigated the FEC fiasco, Sharpton spoke in Boston at the Democratic National Convention and brought the house down. While his presidential hopes are likely gone for good, Sharpton is still a major political power player. His close relationship with former President Barack Obama sits in stark contrast to his adversarial relationship with longtime acquaintance, Donald Trump. In response to Trump's tweet labeling him "a con man... always looking for a score," the Reverend quipped back during a press conference, "If he really thought I was a con man, he'd be nominating me to be on his cabinet."

He was one of the first black ministers to call for LGBT rights

Al Sharpton's calling to the cloth came early; he was preaching before he even learned to read. The future reverend delivered his first sermon, "Let Not Your Heart Be Troubled," in 1958 at the ripe old age of four, and he was ordained a Pentecostal minister at age ten. He was ordained by the Baptist church in the 1990s, when he began preaching again.

If there's one thing Al Sharpton knows, it's how to rile up a crowd, and an ABC News forum for 2004 Democratic Presidential Candidates (via Washington Post) was no exception. When asked about gay marriage, he said the question was "like asking me if I support black marriage or white marriage. The inference of the question is that gays are not human beings and cannot make a decision like other human beings." Such a blunt answer was politically courageous, being that this was several years before marriage equality was believed to be remotely possible.

At the National Black Justice Coalition's Black Church Summit in 2006, Sharpton exhibited the same chutzpah by insisting Black churches need to welcome LGBT people, which NPR pointed out was "a complex relationship" at the time. The Advocate reports Sharpton said, "The way you build coalitions is with mutual interests. I think it would be wise and morally sound to share our battles [with the LGBT community]." Sharpton seems to enjoy building unexpected bridges toward the greater good.

James Brown singularly shaped Al Sharpton's image

A chance meeting between an 18-year-old Al Sharpton and The Godfather of Soul in 1973 altered the course of Sharpton's life. Legendary performer James Brown's son, Teddy, who was involved in Sharpton's National Youth Movement organization in New York City, tragically died in a car accident. "[Brown] came and did a [memorial] benefit for my organization for Teddy," Sharpton told the Times-Herald Record. "Then two weeks later, he took me on Soul Train with him...It don't get no better than that in the 'hood." Brown then took the teenage Sharpton, who had been abandoned by his father at age nine, under his wing, beginning a decades-long surrogate father-son relationship.

Sharpton owes a lot to Brown. He met his second wife, Kathy Jordan, one of Brown's backup singers, while traveling on tour with Brown. NPR reports Brown advised Sharpton not to get into the entertainment industry, but that didn't stop Brown's intoxicating stage presence from rubbing off onto Sharpton. An infamous showman, Brown taught his mentee what is perhaps both men's greatest skill: how to command an audience. Sharpton wrote in his 2013 memoir, The Rejected Stone, that Brown suggested Sharpton sport his hairstyle and persuaded him to shorten his name from Alfred to Al.

Sharpton relayed the most unforgettable piece of advice Brown ever gave him to NEWSONE in 2012. He said, "If you do you, you can't miss because can't nobody do you like yourself."

Al Sharpton and Strom Thurmond share a 'shocking' connection

Strom Thurmond, who served as South Carolina's United States Senator for 48 years, was a well-documented segregationist, who, throughout his entire life, hid the fact that, at 22, he fathered a daughter with his father's 16-year-old Black maid. During a 2007 press conference (via NPR), Sharpton, a highly-recognizable figure in civil rights, revealed his own connection to Thurmond, describing it as, "the most shocking thing in my life." Sharpton's great-grandfather, Coleman Sharpton Sr., had been enslaved by a relative of Thurmond at an Edgefield, S.C. plantation.

Sharpton told The Seattle Times, "Just now, I was going through the airport in Miami and a guy saw me and asked for an autograph, and I stopped to give it to him, and it hit me: I was writing my name because my great-grandfather was owned by a Sharpton. Every time I look at my name, I'm looking at the contract that America provided for us." Slaves received their surnames from their owners. Alexander Sharpton was married to Julia Thurmond Sharpton, Strom Thurmond's first cousin twice-removed, and that marriage provided Al Sharpton's family with that surname. Sharpton and his ex-wife, Kathy Jordan, have two children, Dominique and Ashley, who carry on the Sharpton name. He waxed philosophical when he made the announcement, saying, "The story of the Thurmonds and the Sharptons is the story of the shame and the glory of America."

Al Sharpton lost 176 pounds in four years

Al Sharpton's first foray into weight loss was during a 43-day hunger strike in Vieques, Puerto Rico, where he was arrested in 2001 for protesting U.S. Navy bombing exercises. He lost 40 pounds, but it all came back during his 2004 presidential campaign. In 2006, he told People that his daughter asked him, "Dad, why are you so fat?" That was all it took for him to decide to make a change. "I grew up in civil rights and politics, so I'm pretty thick-skinned," he said. "But when your daughter says it, I started being conscious."

He started by slowly "weaning himself off" of unhealthy foods he loved, and he now follows a strict diet regimen, mostly-vegetarian, and just "one solid meal" per day. "It's always the same salad: lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers, onions, two or three [hard-boiled] eggs cut in and balsamic vinaigrette dressing," he explained to People, adding that he also eats "whole wheat toast" and fish on weekends because his doctor insisted he incorporate more protein into his diet. While that sounds restrictive, Sharpton told NPR, "I don't even feel it. It's normal to me now." And more than just his routine has changed. "I've had to get a whole new wardrobe," he told the outlet, adding, "I've got a guy on Soho who makes Italian suits well, especially those 'skinny pants' y'all call them." Wanna bet a dollar he still wears the track suits at home?

The Tawana Brawley case nearly ruined Al Sharpton

In 1987, Al Sharpton was perfectly perched to launch an effective career in advocacy. He had just successfully advocated for the prosecution of nine white people who angrily chased a 23-year-old Black man Michael Griffith onto a Howard Beach, New York freeway, where he was killed by a moving car. So, when Sharpton heard 15-year-old Tawana Brawley had accused six white men of abducting and raping her, he saw an opportunity to play a similar role on her behalf.

Had things gone differently, Sharpton might have emerged a hero. Instead, a grand jury determined Brawley had fabricated the accusations, fearing her stepfather's angry reaction to a broken curfew. Dan Zegart, a reporter who covered the case, described the Brawley case as "this unbelievable, theatrical performance that went on for months and months." Sharpton even went so far as to accuse prosecutor Steven Pagones of being one of the perpetrators. Pagones sued Sharpton and Brawley for defamation and won (via NPR). Sharpton paid his $65,000 share of the judgment with help from supporters, and Brawley is reportedly still paying her share through garnished wages.

Sharpton refuses to apologize for believing Brawley, but says he learned a lesson about public accusations. He told Vanity Fair "I've thought about [the accusations against Pagones] a million times. I wrestle with his life being upended." The disastrous denouement of the Tawana Brawley case remains, for some, a defining moment in Sharpton's career.

Forgiveness is certainly a virtue of Al Sharpton

A teenage Yusef Hawkins was murdered in 1989 when he went to check out a used car in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn. A group of white men mistakenly thought he was dating a white woman in the neighborhood, and they shot and beat him to death. The Grio reports only two of the eight men charged served time in prison. Joseph Fama was convicted of second-degree manslaughter, and Keith Mondello was convicted of weapons possession, discrimination, unlawful imprisonment, and rioting. Mondello was released in 1998. Fama is due for release in 2022. Sharpton saw the acquittal of the other six men as an opportunity to once again advocate for people of color, and he organized a march to protest the verdict.

The day of the march, Sharpton was, as he wrote in the Daily News, "stabbed in the chest by a white male in Bensonhurst on the other side of Brooklyn for leading a peaceful march protesting the racial killing of 16-year-old Yusuf Hawkins." Sharpton says he struggled with how to respond. "My emotions told me to be angry...My training told me otherwise. Having grown up in the aftermath of the movement of Dr. Martin Luther King... I had been taught forgiveness and reconciliation." Michael Riccardi was convicted of stabbing him. Sharpton spoke at the sentencing hearing to ask for leniency, but the judge gave Riccardi the maximum sentence.

Sharpton drew attention to 'Driving While Black'

According to The New York Times, "driving while Black" refers to the racial profiling of people of color by police, who pull over a disproportionate amount of African American drivers, especially in affluent areas. Sharpton founded the National Action Network (NAN) in 1991 with the purpose of exposing racial profiling and police brutality. In a 2012 piece for NEWSONE, Sharpton claimed that NAN helped draw attention to this all-too-frequent phenomenon by "populariz[ing] the phrases 'racial profiling' and 'driving while Black.'"

Sharpton was even throwing the term around way back in 2000, at a NAACP luncheon. "Many of us try to act like the struggle is over, but we've got more black men in jail than in college, and there are still gaps in incomes between blacks and whites," he said (via The Baltimore Sun), adding, "Hollywood is still racist ... there's still driving while black, shopping while black, going to the airport while black, going down the highway while black and breathing while black. The question is: Where is our response?" Enter, Al Sharpton.

What was Al Sharpton's involvement with the FBI?

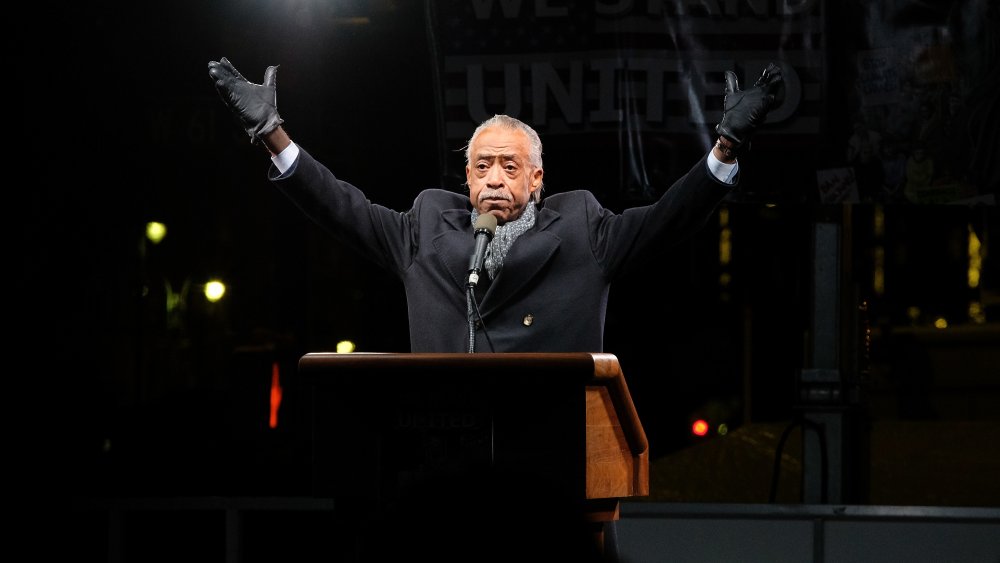

The above image is from a 1983 FBI surveillance tape, in which Al Sharpton was recorded talking to an undercover FBI officer undercover who was posing as a drug dealer. Characterizing the scandal as "one of his lowest moments," Vanity Fair reported that the sting operation was actually aimed at Sharpton's good friend, boxing promoter Don King. Sharpton was on tape discussing a cocaine deal, but he allegedly did not say anything that would have been cause for his arrest. "They tried to entrap me on tape — and by their admission, they didn't — to commit a crime," Sharpton told the outlet, adding, "I answered all their questions and did whatever they wanted with Don King's investigation."

Five years later, in a turn that surprised many, a Newsday article reported Sharpton was an FBI informant regarding organized crime. Some hypothesized he had done so to avoid prosecution in the King sting, but Sharpton denied that to Vanity Fair, saying he offered information to the agency after the mafia "threatened his life in a music-business turf war."

HBO later aired the FBI's surveillance video on Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel in July 2002, prompting Sharpton to file a $1 billion dollar defamation lawsuit. It's unclear what, if anything, happened with that lawsuit, but in June 2003, Salon reported Sharpton had still not received "a cent in damages."

Is Al Sharpton an anti-Semite?

Tensions between the Jewish and Black communities in Crown Heights, Brooklyn were already high in 1991 when a car accident made them boil over. According to The Jewish Star, Yosef Lifsh, a Hasidic man driving one of three cars in a motorcade for a Grand Rabbi, was in an accident that launched his station wagon onto a sidewalk where two Black children were playing. One was injured, the other, Gavin Cato, died. Lifsh got out of the car to try to help the children, but neighbors began physically attacking him. In the days following the incident, violence erupted in the community, leading to the brutal murder of Yankel Rosenbaum at the hands of a group of Black teens.

Al Sharpton, as he wrote in a Daily News essay, showed up at the request of Cato's father, and led a march of protesters that was filled with anti-Semitic signs and chants. Sharpton also delivered the eulogy at Cato's memorial, which was accused of having inflammatory, anti-semitic sentiments. Push-back against Sharpton was swift, and this incident has come back to haunt Sharpton many times. A resolution was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in 2000, condemning Sharpton for his actions in Crown Heights, as well as other examples of his alleged overt anti-Semitism. When Sharpton was invited to speak at a Jewish conference in 2019, the brother of the slain Yankel Rosenbaum co-wrote an essay in the Washington Examiner, slamming Sharpton for participating in actions "that terrorized the Jewish community for nearly four days."

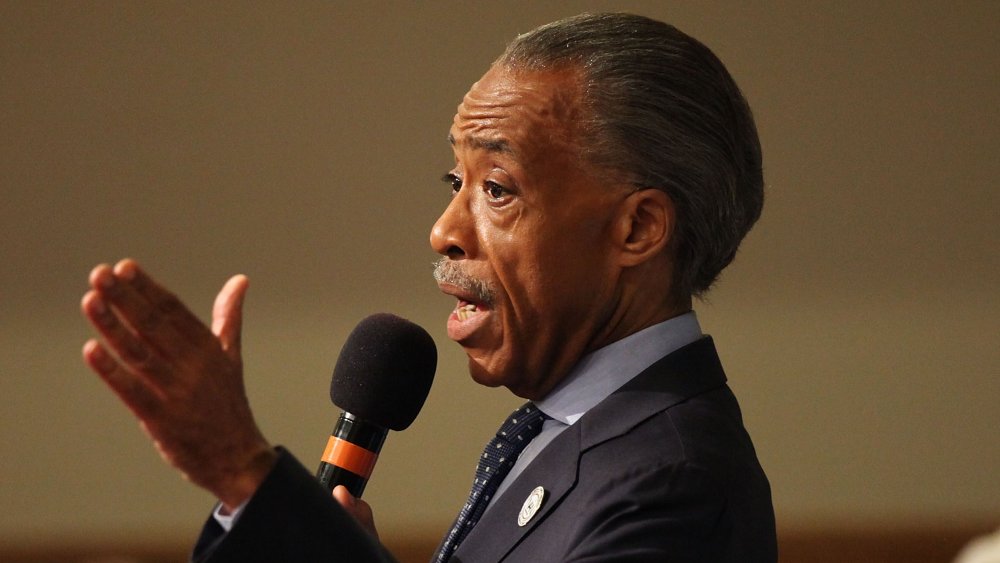

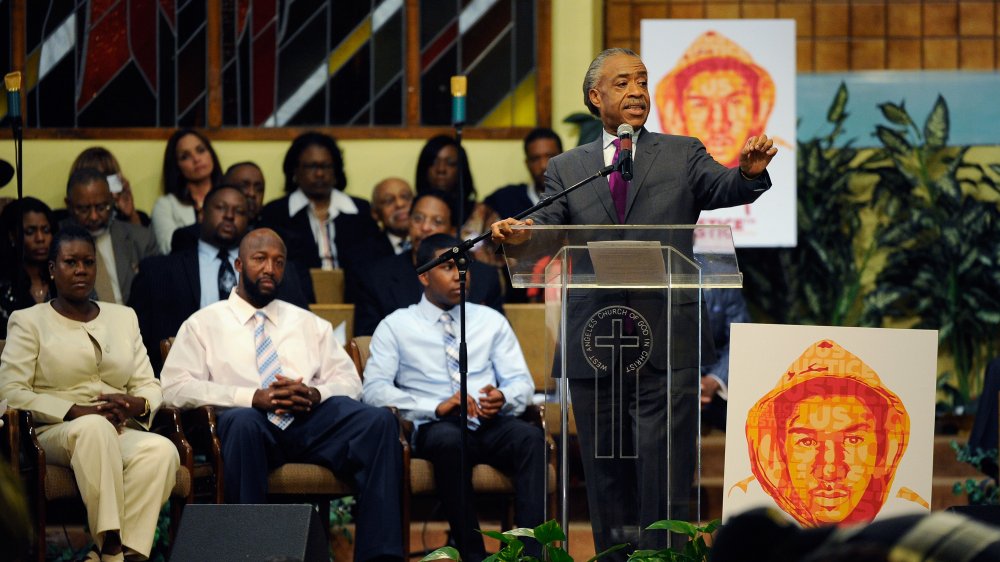

Al Sharpton did not take down 'stand your ground'

Following Trayvon Martin's 2012 death, Al Sharpton led protests when the neighborhood watchman who shot Martin, George Zimmerman, had not yet been arrested. Families often reach out to Sharpton to draw attention to their case, and "Black Lives Matter" is a mantra he has exuded throughout his decades-long career. While this is often criticized as exploitative, Sharpton isn't bothered by naysayers who roll their eyes when he rushes to tragedies. "What I always say when they say I'm an ambulance-chaser," he told the New York Times, "is that I'm the ambulance. They knew that I would come."

Ending police and race-based violence is one of Sharpton's key issues, but he is not without his critics, like New York Police Union's Pat Lynch, who called Sharpton "one of the chief extremists fanning the flames of anti-police sentiment for his own gain" (via the Daily News). Sharpton did, in fact, seize on Zimmerman's case to protest against Florida's controversial "stand your ground" laws, which The New York Times pointed out actually did not factor into Zimmerman's defense and ultimate acquittal. Nonetheless, Sharpton led rallies against the policies, describing them (via WUSF Public Media) as a pass to "shoot first and then ask questions later" and "a violation of our civil rights." Florida, apparently unmoved by Sharpton's activism, actually ended up strengthening "stand your ground."

Al Sharpton isn't the best financial manager

Al Sharpton admits that "fiscal manage[ment]" is not his strong point. "As with most civil-rights groups, we struggle to raise money. Sometimes we over-extended ourselves," he told Vanity Fair, adding, "One of the things about being raised by everybody from James Brown to Jesse Jackson, who all had tax issues, [is] I never learned administration."

On top of his publicly reported campaign finance transgressions, it is also alleged that Sharpton still holds a debt of more than $900k from that campaign. But it isn't just campaign finance questions that dog him. Vanity Fair reports Sharpton faced 67 fraud and larceny charges after the Tawana Brawley case, but he was acquitted of them all. By 2012, Sharpton had to enlist attorney Michael Hardy to take over NAN's fiscal management and help settle several lawsuits, while also slowly negotiating and reducing Sharpton's personal and organizational debts. The New York Times reported in 2014 (via CNN), that Sharpton, together with his for-profit companies, owed more than $4.5 million in unpaid state and federal taxes. In 2015, Sharpton paid a large chunk of that, and NAN paid its entire IRS debt.

Considering all of that, perhaps it's not so unusual that, despite the New York Post reporting Sharpton's 2018 salary from NAN at over $1M, and hundreds of thousands in additional income from public and media appearances, Celebrity Net Worth estimates his net worth at only $500k.