Sports Stars Who Died Right Before Fans' Eyes

While top-level professional sports stars can seem superhuman, they are a little like the characters from "Watchmen": they don't actually possess any magical powers that set them apart. There are no radioactive spider bites or secret experiments gone wrong (Dr. Manhattan aside). They're fully human, just better.

Take once-in-a-generation athlete LeBron James. As of this writing, Bron is 36 years old. He stands almost six foot nine and weighs nearly 260 pounds, according to Bleacher Report. So how is it he's been running up and down basketball courts, winning chips, and catching-above-the-rim lobs for over two decades and has never suffered a major injury? No Achilles tears. No ACL explosions. Nothing that has ever cost him a season. With all that size bearing down on his joints, how is this even possible? Even he knows it's odd. "I don't get tired," James quipped to reporters in 2021.

That's what makes it all the more jarring when one of these extraordinary beings becomes mortal before our very eyes. We worship athletes because they do things we can only imagine — and usually only after three or so overpriced arena beers. So seeing them fall is a kind of shock that can stick with fans for a lifetime. These athletes died before their chosen arena's eyes and gave us all a sad reminder that even our heroes are human too.

Len Bias

Len Bias might've been the best NBA superstar that never was. Instead, as ESPN writes, he became a symbol, "a one-man deterrent, the athlete who reminded everyone just how dangerous drug use can be."

Bias stood six-foot-seven and a solid 221 pounds — a stout frame for a 22-year-old prospect yet to really fill out. As a senior at Maryland during the 1985-86 season, he averaged over 23 points per game — a monster stat in the shorter format of the collegiate game, and before three-pointers dominated the game. Bias was also a consensus All-American and ACC tournament MVP. After his standout senior season, the skilled small-forward was selected second in the NBA draft by the Boston Celtics, according to ESPN.

Only two days later he would be dead. Bias was partying in a dormitory with friends and teammates, likely celebrating his high-draft status. That's when he ingested "an unusually pure dose" of cocaine, according to the Los Angeles Times. Bias, who was otherwise healthy and had just passed a physical performed by the Celtics organization, was dead within minutes. The drug, according to the medical examiner, "interrupted the normal electrical control of his heartbeat, resulting in the sudden onset of seizures and cardiac arrest." In a Sports Illustrated feature about the tragedy, Celtics star Larry Bird said, "It's the cruelest thing I've ever heard."

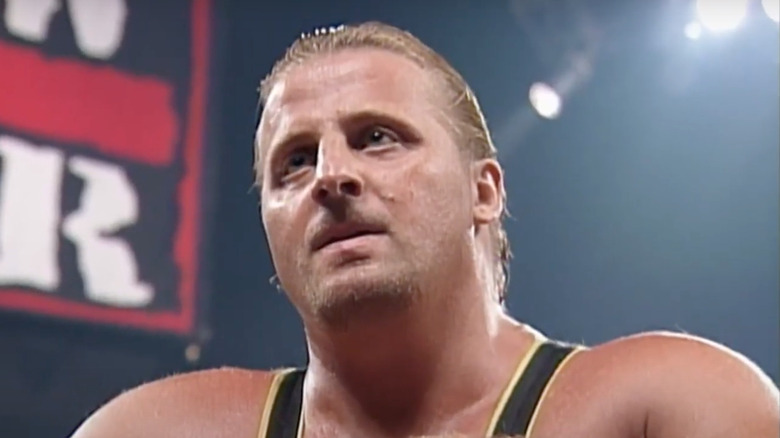

Owen Hart

If people didn't realize there's a big difference between pro wrestling being "fake" and being safe, they found out in 1999 when WWE star Owen Hart died in front of 16,000 fans in Kansas City, Missouri. The accident was not caught on the pay-per-view broadcast, but everyone in Kemper Arena witnessed Hart's passing.

On a 2021 episode of "Lucha Libra Online" (via The Sports Rush), referee Jimmy Korderas remembered standing ringside cleaning up after a messy hardcore match when he felt some falling debris graze his back. He reflexively ducked as he heard some screaming he later surmised was Hart telling another wrestler to get out of the way. "When I turned around, he was there, lying on his back on the corner of the ring," Korderas recalled. "I called him a few times and got no response. That's where I panicked and started screaming for help from anybody."

Owen Hart, aka "Blue Blazer," was the little brother of the well-known Bret "The Hitman" Hart. In a stunt he had performed many times, the younger Hart was being lowered from the arena ceiling into the ring on an allegedly improper wire that somehow failed and dropped him 80 feet to his death, according to CBS Sports. He was only 33 years old and left behind a wife and two children. His widow, Martha Hart, reached a settlement of $18 million with the WWE. She maintains that the incident was the company's fault, telling CBS Sports "the stunt itself was so negligent."

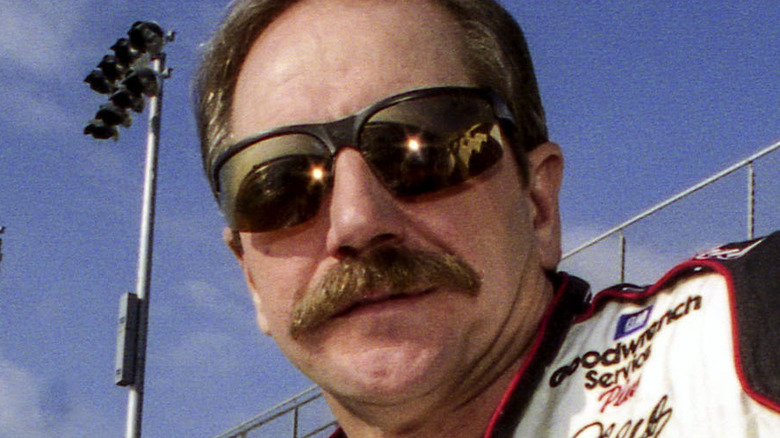

Dale Earnhardt Sr.

"Dale Earnhardt was first — at last," wrote ESPN in 1998 of the legendary NASCAR driver, also known to fans and competitors alike as "the intimidator." Although winning past races in Daytona, he'd never won the 500, the sport's biggest spectacle, until then. But at 46 years old, the iconic driver finally ended the race as the victor. "Yes! Yes! Yes!" he shouted in celebration with his crew (via ESPN). "We won it! We won it! We won it!"

Three years later tragedy struck at that same track. Earnhardt was making a signature aggressive move on the final curve, battling through heavy traffic and traveling over 180 miles per hour. Suddenly, he lost control and smashed into the wall. He sustained multiple severe injuries, and doctors pronounced him dead that evening, according to the Orlando Sentinel. It appeared blunt force trauma had killed him instantly.

NASCAR's biggest star died in front of nearly 200,000 screaming fans. Earnhardt was not wearing a full face mask during the crash and his seat belt also failed, according to The New York Times. As Jalopnik wrote, the incident "launched an increased focus on racing safety" in NASCAR. The full autopsy later confirmed he died of a skull fracture. He was 49.

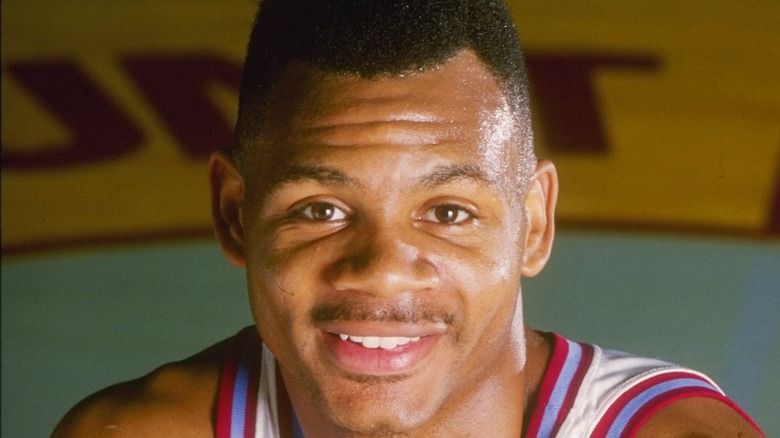

Hank Gathers

During the first game of the 1990 WCC conference tournament, Loyola Marymount's Hank Gathers scored 28 points in his team's blowout victory. Gathers had led the country in scoring and rebounding that season. "He was an unbelievable physical specimen," future NBA coach and college rival Erik Spoelstra told the Los Angeles Times.

Gathers also had a heart condition but the 23-year-old NBA prospect was brimming with confidence. "I'm the most doctor-tested man alive," he quipped, according to ESPN. "I feel great. I'm in the best shape of my life. My mom's out here, and I'm looking forward to some good home cooking." Gathers, however, was also weaning off his heart meds which he felt made him sluggish.

Days later on March 4, 1990, Loyola was facing Portland. Gathers got loose on the wing and caught a long lob for a thunderous jam. Thousands of fans roared. But as the forward slapped fives and ran back on defense, the six-foot-seven, 220-pound star collapsed so suddenly he was, "unable to make any effort to break his fall," ESPN recalled. Gathers tried to get up but again collapsed and lost consciousness. "The absolute silence in the gym after he fell," Spoelstra would remark to the LA Times years later, "it's something I'll never forget." Gathers was later pronounced dead at a local hospital. An autopsy found no illicit drugs in his system, according to The New York Times. However, also absent were the prescribed medications for his chronic heart condition.

Maxim Dadashev

Maxim Dadashev had never lost a professional boxing match on the night he died. The Russian prospect had captured a silver medal at the World Junior Championships in 2008. He then turned pro in 2016, fighting at 140 pounds, and won 13 consecutive fights, 11 by knockout.

When he stepped into the ring in 2019, even though he was facing a brutally heavy-handed whirlwind named Subriel Matías, he had every reason to be confident. But over the course of nearly a dozen rounds, Matías' relentless power wore Dadashev down — but somehow, he did not fall. As ESPN recounted, Dadashev's cornerman begged Maxim to let him call it off after the 11th round, and the fighter collapsed as he was leaving the ring. He was transported to a hospital for brain injuries, and less than a week later, the AP reported he died. He was only 28.

"He was a very kind person who fought until the very end," his wife, Elizaveta Apushkina, who lives in Russia with their young son told The New York Times. "Our son will continue to be raised to be a great man like his father." Thankfully, Russian boxing pledged to help Max's widow. "He was our young prospect," Umar Kremlev, the secretary-general of the Russian Boxing Federation, said in a statement. "We will fully support his family, including financially."

Vladimir Smirnov

Sticking with the theme of Russian tragedy is the shocking and gruesome death of iconic Olympic fencer Vladimir Smirnov.

Smirnov may have been the best fencer in the world in the early 1980s, according to Portable Press. When the US boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, the Ukrainian-born fencer took home three medals for the Soviet Union, including gold in the individual foil, a one-on-one format with the thinner — and it turns out sharper — of the two fencing blades. The next year he again proved his supremacy by winning the 1981 World Championship.

In 1982 Smirnov was looking for back-to-back titles at the World Championships in Rome. The Soviet star went up against another of the world's best in the first round, West Germany's 1976 Olympic gold medalist, Matthias Behr. That's when tragedy struck. Behr's thin foil blade somehow snapped, and despite the thick padding fencers wear, crisply white but hardy — something like beekeeper assassins — the jagged blade jutted through Smirnov's mesh mask, according to The New York Times. The broken tip went through Smirnov's eyeball and went into his brain. Nine days later, the 28-year-old champ died. As Portable Press noted, his death "led to sweeping changes in fencing," such as upgrading the materials used in both swords and padding, trading carbon for steel blades, and making masks of kevlar. Only seven fencers have ever died in elite competitions, and none since the legendary Ukrainian lost his life.

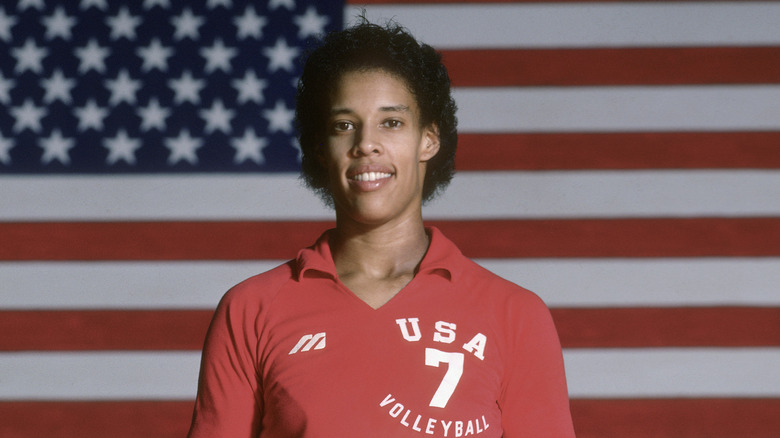

Flo Hyman

US women's volleyball was in sorry shape in the 1970s. The American team failed to even qualify for the 1972 Olympic games, according to the Los Angeles Times. But when Flo Hyman joined the team in 1974, that all changed, taking team USA, "from recreational into an internationally competitive program," according to former national team coach Pat Zartman. The 6'5" Hyman went straight from high school to world-class player, and by 1980, the US women's team was considered the Olympic favorite. However, Hyman's dreams were dashed when the US boycotted that year's games in Moscow over Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union.

Undaunted, Hyman stuck with the sport. As the Los Angeles Times recounted, Flo was the oldest female player in 1984's Games but still led her team to a silver medal. Two years later, Hyman started playing for a Japanese women's league. During the third game of a match in 1986, she collapsed as she sat on the bench.

"There wasn't anything strange about her health before the match. She didn't have any health problems," team director Yasuhiro Doi told the AP (via the Los Angeles Times). However, Hyman's family didn't buy the initial cause of death and an autopsy later revealed she had an undiagnosed case of a rare disorder called Marfan Syndrome. This likely contributed to her great height, but also weakened her heart. Hyman was 31 years old.

Fran Crippen

Fran Crippen wasn't a superstar like Michael Phelps, but he may very well have been on his way to Olympic glory when he died in an open water competition. The 11-time All-American medaled at numerous international indoor swimming competitions, according to his website, but in 2006 made the transition to open water competitions to pursue his Olympic aspirations. Crippen just narrowly missed the cut to represent Team USA in 2008 and returned home to Pennsylvania to pursue coaching. It was there he reconnected with his own childhood swim coach and re-dedicated to his sport, becoming a six-time national outdoor champion.

But Crippen wanted another crack at Olympic gold too, which meant staying active. In October of 2010, this Aquaman was competing in Abu Dhabi, well known for its blazing temperatures and soupy waters. Crippen told a friend earlier in the day the air was 100 degrees and the water a swampy 87, according to ABC News.

Like many swimmers, Crippen was also known to consume 10-15 packs of caffeinated energy gel during his races — the equivalent of five cups of coffee. It's unclear why exactly he suddenly sank to the seafloor only to be pulled out by rescue divers, but experts believe it was either cardiac arrhythmia or simply drowning after passing out. "Both were directly related to overexertion, which is a terrible garbage-can diagnosis and does not speak to what happened," Dr. Mark Morocco of the UCLA School of Medicine told ABC News. Crippen was 26 years old.

Jose Flores

A shocking accident in 2018 took the life of one of the greatest jockeys to ever saddle up. Jose Flores ran nearly 30,000 races in his career, according to CBS Sports. He won over 4,000 first-place finishes and racked up $64 million, the most in the history of his home track.

Five years after this legend of the paddock was inducted into the Parx hall of fame, he mounted up at his Bensalem, Pennsylvania home field, as he'd done so many times before. There is no video of the incident but witnesses say Flores' horse fell forward, throwing the rider headfirst into the ground causing, as CBS Sports recounted, "massive head trauma." Two other riders went down in the chaos, but both walked away with only minor injuries.

Flores was not so lucky. He held on for three days at Aria Frankford Torresdale Hospital but the decision was made to take him off life support. "It's unbelievable, just sickening," Scott Lake, a long-time trainer at Parx and friend of Flores since 1991 told The Philadelphia Inquirer. "He was just tremendous, a nice guy, always a professional." Fellow jockey Kendrick Carmouche recalled a tragically prophetic conversation he had with Flores just before his friend's death, the doomed rider remarking, "You know, I found a good wife. I just hope I don't get hurt." Flores was 58 years old and left behind his spouse Joanne McDaid-Flores, as well as their 7-year-old son Julian — plus two children from a previous relationship.

Ayrton Senna

If Nascar is the Budweiser of racing, Formula One is the Champagne — as in actual Champagne, from the Champagne region of France. But it turns out, bougie racing isn't any less dangerous than its more working-class American cousin.

The Brazilian speedster Ayrton Senna has been described by his luxury auto brand McLaren as "arguably the greatest F1 driver of them all." In his tragically shortened career that spanned 1984 to 1994, he won three World Championships and 41 races out of 161 overall — a staggering percentage in a highly competitive sport.

On May 1, 1994, Senna was competing on live television for another world championship when his car took a sudden turn off the track at Imola Circuit in Bologna, Italy, and smashed into the crash barriers. Medics found a piece of "debris had pierced his helmet, causing multiple fractures at the base of his skull," according to VICE. Ayrton was so famous, and so mourned, the outlet wrote "his state funeral was broadcast live on television in Brazil, while the government declared three days of national mourning." Ayrton wasn't the first racer to die at a Grand Prix, and his death at age 34 instigated a twisty search for culpability. Manslaughter charges were eventually brought against three event organizers and Ayrton's own team boss, though the cases languished in Italian courts, and the truth of what actually caused the crash may never be known.

Wouter Weylandt

Professional cycling is extremely dangerous, Bleacher Report describing riders as lined up "elbow to elbow" battling for position. They often reach speeds of 37 MPH under their own power, with nothing more than their helmets and thin neoprene suits to protect from the tangle of bikes that can result in brutal crashes. But in tour cycling, the descent from exhausting mountain climes is the most dangerous leg. On the one hand, it's a brief reprieve from the painful exertion of the sport, on the other, riders can reach speeds of well over 60 MPH where one mistake is all it takes.

That's what took the life of Belgian cyclist Wouter Weyland in 2011 when he was making his descent in the Giro d'Italia from the Passo del Bocco. The broadcast didn't catch his fall but a helicopter camera discovered his body lying motionless on the cement, "a pool of blood spreading around his still-helmeted head," according to Bleacher Report. The broadcast quickly cut away.

Medics arrived promptly but Weylandt was beyond help. Doctor Giovanni Tredici told ESPN, "He was unconscious with a fracture of the skull base and facial damage. After 40 minutes of cardiac massage, we had to suspend the resuscitation because there was nothing more we could do." Weylandt's death was the first at this Italian race in 25 years, and the first at any of the major "showcase tours" in 16 years. Tragically, his girlfriend was pregnant at the time. He was only 26 years old.

Duk-koo Kim

One of the most famous deaths in the ring of all time was that of Duk-koo Kim at the hands of the legendarily heavy-handed Ray "Boom Boom" Mancini.

Ray Mancini took his nickname from his father, also a decorated fighter, during World War II. Mancini ended his career on four straight losses, but before that, had a stellar 29-1 record, with 23 of those wins coming by vicious knockout. The granite-fisted lightweight, (135 pounds) won a world title in 1980, according to NPR, which made him a star in the sport.

As NPR recounted, Mancini took on Duk-koo Kim in his second title defense in 1982. Mancini floored the South Korean fighter in the 14th round, and Kim died four days later at only 27. The incident badly shook Mancini and changed boxing forever. "It haunted me, why was it [Kim] and not me?" Mancini mused to the outlet while lauding the bravery of his opponent. "He was giving as good as he was getting. And who's to say it wouldn't be me next time?" Only weeks later, The World Boxing Council voted to change their title fights from 15 rounds to 12 rounds, according to The Washington Post. The WBC said the move would "prevent boxers from suffering irreparable injuries." While ring deaths have not abated, the shorter format was adopted by all other major boxing organizations. Kim's death has saved countless fighters from needless late-round beatings.

João Carvalho

In 1996 as mixed martial arts grew to prominence following the birth of the sport's most popular league, Dana White's UFC, the late Senator John McCain denounced the entire endeavor as "human cockfighting" and made it his mission to ban it from the broadcast airwaves, according to Slate. By 2007, however, McCain had changed his tune. The sport was firmly established and even the famous Senator admitted to NPR sanctioned martial arts competitions had made "significant progress" (via MMA Fighting). As of this writing, despite nearly three decades of UFC events, not a single death has occurred inside the organization's signature Octagon ring. No major boxing organization can make that claim

That's not to say MMA, in general, isn't dangerous as heck. Numerous deaths have occurred in smaller promotions. And in fact, in 2016, Charlie Ward, a teammate of the sport's biggest star, Connor McGregor, inadvertently beat to death 28-year-old European prospect João Carvalho in a brutal bout, according to the Independent. The fight was stopped in the third round and Carvalho was rushed to the hospital but it was too late. He died 48 hours later, after having taken some 41 shots to the head.

McGregor was shaken by the tragedy, and used his immense Facebook platform to send the lesser-known fighter's family his best wishes (via Sports Joe): "To see a young man doing what he loves, competing for a chance at a better life, and then to have it taken away is truly heartbreaking."

Rondel Clark

One more MMA death is instructive for a lesser-known danger lurking inside this brutal blood sport. UFC and MMA fighters, in general, will routinely cut as much as 20 pounds the day before bouts to make their contracted weights. Fighters then have roughly 24 hours to recover from this all-too-common sauna and sweat process that sometimes causes athletes to literally collapse on the scales.

MMA sanctioning bodies have come up with various rules to limit extreme weight cuts, with little success. In 2016 the UFC all but banned the use of IVs for rehydration, according to SB Nation. The problem is these kinds of rules are hard to enforce behind closed doors, and cutting weight to be the bigger athlete in the fight is such a competitive advantage, if IVs are banned, many fighters will simply continue drastic cuts, skip proper rehydration, and fight anyway.

These rules also don't apply to independent shows which often aren't well regulated. As MMA Fighting recounted, Rondel Clark was competing in only his second MMA fight at a local show in Massachusetts in 2017. After a purported 15-20 pound weight cut he lost via TKO in round three without taking much punishment — which can be a sign of dehydration. He died three days later, at age 26. The autopsy would blame a mix of overexertion and dehydration, according to MMA Fighting, and his mother would agree. "It was because of the weight cut before the fight," Arianne Clark told the site.

Scott Kalitta

"I live my life a quarter-mile at a time, nothing else matters," grunts Vin Diesel in a very fast and very furious racing film that would inspire roughly as many sequels as remaining financially viable movie theaters. But this line isn't just Hollywood bravado; some athletes do actually live their life this way — and some have paid the ultimate price.

In 2008 a freak crash at the Lucas Oil NHRA SuperNational drag racing event took the life of veteran driver Scott Kalitta. The two-time champion "Funny Car" driver was the son of one of the founding fathers of the sport, according to ESPN — as well as one of the most "feared" racers in the game. "If I'm in Top Fuel, the one thing I don't want to see is that Kalitta car pulling up in that other lane," admitted fellow driver Bob Frey (via ESPN).

A lot changed between Kalitta's father's DIY era and his. The younger racer was driving "one of the safest and technologically advanced racing machines in professional motorsports," when something went tragically wrong. According to the police report, a catastrophic mechanical failure caused a sudden fiery explosion, propelling the racer past the finish line at over 300 miles per hour. Kalitta's car began coming apart and his parachute deployed but still careened into a gravely "run-off" area at over 125 MPH. Scott Kalitta was 46 years old and left behind a wife and two sons.